Plants usually convert light into chemical energy with a photosynthetic efficiency of 3-6%.[21] Actual plants' photosynthetic efficiency varies with the frequency of the light being converted, light intensity, temperature and proportion of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, and can vary from 0.1% to 8%.[22] By comparison, solar panels convert light into electric energy at a photosynthetic efficiency of approximately 6-20% for mass-produced panels, and up to 41% in a research laboratory.[23]

Evolution

Early photosynthetic systems, such as those from green and purple sulfur and green and purple non-sulfur bacteria, are thought to have been anoxygenic, using various molecules as electron donors. Green and purple sulfur bacteria are thought to have used hydrogen and sulfur as an electron donor. Green nonsulfur bacteria used various amino and other organic acids. Purple nonsulfur bacteria used a variety of non-specific organic molecules. The use of these molecules is consistent with the geological evidence that the atmosphere was highly reduced at that time.[citation needed]

Fossils of what are thought to be filamentous photosynthetic organisms have been dated at 3.4 billion years old.[24]

The main source of oxygen in the atmosphere is oxygenic photosynthesis, and its first appearance is sometimes referred to as the oxygen catastrophe. Geological evidence suggests that oxygenic photosynthesis, such as that in cyanobacteria, became important during the Paleoproterozoic era around 2 billion years ago. Modern photosynthesis in plants and most photosynthetic prokaryotes is oxygenic. Oxygenic photosynthesis uses water as an electron donor which is oxidized to molecular oxygen (O2) in the photosynthetic reaction center.

Symbiosis and the origin of chloroplasts

Several groups of animals have formed symbiotic relationships with photosynthetic algae. These are most common in corals, sponges and sea anemones, possibly due to these animals having particularly simple body plans and large surface areas compared to their volumes.[25] In addition, a few marine mollusks Elysia viridis and Elysia chlorotica also maintain a symbiotic relationship with chloroplasts that they capture from the algae in their diet and then store in their bodies. This allows the molluscs to survive solely by photosynthesis for several months at a time.[26][27] Some of the genes from the plant cell nucleus have even been transferred to the slugs, so that the chloroplasts can be supplied with proteins that they need to survive.[28]

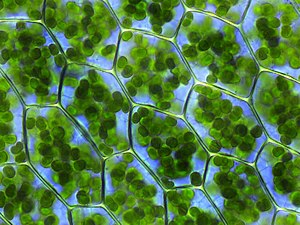

An even closer form of symbiosis may explain the origin of chloroplasts. Chloroplasts have many similarities with photosynthetic bacteria including a circular chromosome, prokaryotic-type ribosomes, and similar proteins in the photosynthetic reaction center.[29][30] The endosymbiotic theory suggests that photosynthetic bacteria were acquired (by endocytosis) by early eukaryotic cells to form the first plant cells. Therefore, chloroplasts may be photosynthetic bacteria that adapted to life inside plant cells. Like mitochondria, chloroplasts still possess their own DNA, separate from the nuclear DNA of their plant host cells and the genes in this chloroplast DNA resemble those in cyanobacteria.[31] DNA in chloroplasts codes for redox proteins such as photosynthetic reaction centers. The CoRR Hypothesis proposes that this Co-location is required for Redox Regulation.

No comments:

Post a Comment